WHEN

Ken Martin, a hat-seller, pays his monthly child-support bill, he uses a

money order rather than writing a cheque. Money orders, he says, carry

no risk of going overdrawn, which would incur a $40 bank fee. They cost

$7 at the bank. At the post office they are only $1.25 but getting there

is inconvenient. Despite this, while he was recently homeless, Mr

Martin preferred to sleep on the streets with hundreds of dollars in

cash—the result of missing closing time at the post office—rather than

risk incurring the overdraft fee. The hefty charge, he says, “would kill

me”.

Life is expensive for America’s poor, with financial

services the primary culprit, something that also afflicts migrants

sending money home (see

article).

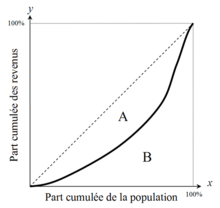

Mr Martin at least has a bank account. Some 8% of American

households—and nearly one in three whose income is less than $15,000 a

year—do not (see chart). More than half of this group say banking is too

expensive for them. Many cannot maintain the minimum balance necessary

to avoid monthly fees; for others, the risk of being walloped with

unexpected fees looms too large.

Doing

without banks makes life costlier, but in a routine way. Cashing a pay

cheque at a credit union or similar outlet typically costs 2-5% of the

cheque’s value. The unbanked often end up paying two sets of fees—one to

turn their pay cheque into cash, another to turn their cash into a

money order—says Joe Valenti of the Centre for American Progress, a

left-leaning think-tank. In 2008 the Brookings Institution, another

think-tank, estimated that such fees can accumulate to $40,000 over the

career of a full-time worker.

Pre-paid debit cards are growing in

popularity as an alternative to bank accounts. The Mercator Advisory

Group, a consultancy, estimates that deposits on such cards rose by 5%

to $570 billion in 2014. Though receiving wages or benefits on pre-paid

cards is cheaper than cashing cheques, such cards typically charge

plenty of other fees.

Many states issue their own pre-paid cards

to dispense welfare payments. As a result, those who do not live near

the right bank lose out, either from ATM withdrawal charges or from a

long trek to make a withdrawal. Other terms can rankle; in Indiana,

welfare cards allow only one free ATM withdrawal a month. If claimants

check their balance at a machine it costs 40 cents. (Kansas recently

abandoned, at the last minute, a plan to limit cash withdrawals to $25 a

day, which would have required many costly trips to the cashpoint.)

To

access credit, the poor typically rely on high-cost payday lenders. In

2013 the median such loan was $350, lasted two weeks and carried a

charge of $15 per $100 borrowed—an interest rate of 322% (a typical

credit card charges 15%). Nearly half those who borrowed using payday

loans did so more than ten times in 2013, with the median borrower

paying $458 in fees. In 2014 nearly half of American households said

they could not cover an unexpected $400 expense without borrowing or

selling something; 2% said this would cause them to resort to payday

lending.

Costly credit does not mix well with lumpy welfare

payments. The earned-income tax credit (EITC), an income top-up for poor

families, is paid annually, as part of a tax refund. The total refund

can run into thousands of dollars, making it worth more than many

families’ monthly pay cheque. Unsurprisingly, cash-strapped households

seek to borrow against this windfall in advance. Regulators have

recently nudged banks away from issuing high-cost short-term loans

secured against imminent tax refunds. But it is still common to borrow

to cover the cost of applying for the EITC. In 2014 almost 22m consumers

used “refund anticipation cheques”, which offer a loan to pay the

filing costs and collect repayment automatically when the refund

arrives. These products typically cost between $25 and $60 for credit

that lasts only a few weeks, according to Chi Chi Wu of the National

Consumer Law Centre, an advocacy group.

How might financial

services be made cheaper for the poor? Mr Valenti sees promise in mobile

banking. But the poor are not yet well placed to benefit from the

mobile revolution, in financial services or otherwise. Only half of

those earning less than $30,000 per year own a smartphone, compared with

70% or more of those in higher income groups. Nearly half those who do

manage it have had to temporarily cancel their service for financial

reasons. That might itself be the result of disparate prices: those with

poor credit ratings rely on pre-paid SIM cards, which unlike normal

monthly contracts do not come with a hefty discount for the handset.

Low

smartphone penetration in turn makes life more expensive in other ways.

The unconnected do not benefit from the cheap communication, education,

and even transport the app economy provides. A quarter of poor

households do not use the internet at all, which makes seeking out low

prices harder.

Price discrimination

Inflation

has also squeezed the poor more in recent years. The prices of items

which soak up much of their budgets—such as rent, food and energy—have

risen faster than other goods and services. Falling oil and energy

prices may be reversing that trend, though typically the poor own fewer

cars, so benefit less from cheaper petrol.

From 2000 to 2013—the

latest year for which figures are available—inflation has been higher

for those in poverty for 139 of 168 months, according the Chicago

Federal Reserve. As a result of this inflation premium, prices rose 3.2%

more for the poor over this period. These figures may understate the

disparity, because they do not include employer contributions to health

insurance, which are widely thought to hold down pay cheques, and make

up a bigger proportion of the total pay of the poor.

The high cost

of being poor has two main implications. First, inequality is worse

than income figures alone suggest. This is true even before

non-financial disparities, such as the implications for health of living

on a low income, are considered. Second, finding ways to reduce these

costs, for instance by making it easier to claim the EITC without

borrowing, or by changing the rules on overdraft fees (which at the

moment are used to cross-subsidise banking for other customers), would

be a cheap way of helping low earners—and bargains are rare for the

poor.

Quand je vois toute les voitures sur nos routes, leurs occupants hommes femmes et enfants, tous les camions transportant les marchandises des producteurs aux consommateurs, tous ceux qui vont à leurs postes de travail, toutes les infrastructures, les immeubles, les bureaux, les magasins, les hôpitaux, les véhicules de transport collectifs et ceux qui les conduisent; quand je vois toutes les maisons, les appartements, chacun avec ses objets et ses biens accumulés depuis des années... Je me dis que nous dépendons tous les uns des autres. Rien ne nous appartient vraiment comme si nous en étions seuls les créateurs. Ce que nous avons et que nous considérons comme notre propriété privée sacro sainte, nous le devons à tous les autres. Nous partageons ainsi tout ce qui est produit, a été produit, et continuera d'être produit.

Quand je vois toute les voitures sur nos routes, leurs occupants hommes femmes et enfants, tous les camions transportant les marchandises des producteurs aux consommateurs, tous ceux qui vont à leurs postes de travail, toutes les infrastructures, les immeubles, les bureaux, les magasins, les hôpitaux, les véhicules de transport collectifs et ceux qui les conduisent; quand je vois toutes les maisons, les appartements, chacun avec ses objets et ses biens accumulés depuis des années... Je me dis que nous dépendons tous les uns des autres. Rien ne nous appartient vraiment comme si nous en étions seuls les créateurs. Ce que nous avons et que nous considérons comme notre propriété privée sacro sainte, nous le devons à tous les autres. Nous partageons ainsi tout ce qui est produit, a été produit, et continuera d'être produit.